His Memory As a Blessing

- Dr. Bob

- May 29, 2019

- 6 min read

Off and on of late, I've been cataloging my library on Library Thing. I'm up to the hardcover K's and, in entering the Nightmares and Dreamscapes by Stephen King, I noted the dedication:

"In memory of THOMAS WILLIAMS, 1926-1991: poet, novelist, and great American storyteller."

and, above it, the author's autograph and brief inscription:

"In Memory of Tom--Stephen King".

And thereby, much like my brief intersection with the late great Harlan Ellison, hangs a tale, perhaps two.

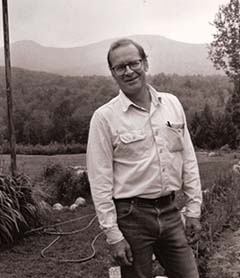

Professor Thomas Williams is, was, the 1975 National Book Award-winning author of The Hair of Harold Roux (1974) as well as seven other novels and short works who sadly passed away in 1990 at the age of 63 -- an age I note with slight disquiet that I myself will reach in two years. Tom was, as described by New York Times critic Orville Prescott:

"a marvelously exact observer of the natural world, of the behavior of men and animals, and of the shape and surface and significance of things... (who) manipulates the English language with love and with controlled power."

Tom's insights extended to writing and, perhaps more importantly, to writers. With them, he shared both empathy and sympathy. Regarding Professor Williams and his novel The Hair of Harold Roux, Stephen King wrote in The Atlantic in 2011:

"He was a wonderful, wonderful novelist. ...The Hair of Harold Roux, which is one of my favorite books, (is) about a writer named Aaron Benham.

Benham says that when he sits down to write a book it's like being on a dark plain with one little tiny fire. And somebody comes and stands by that fire to warm themselves. And then more people come. And those are the characters in your book, and the fire is whatever inspiration you have. And they feed the fire, and it gets big, and eventually it burns out because the book is at an end.

It's always felt that way to me. When you start, it's very cold, an impossible task. But then maybe the characters start to take on a little bit of life, or the story takes a turn that you don't expect ... With me that happens a lot because I don't outline, I just have a vague notion. So it's always felt like less of a made thing and more of a found thing. That's exciting. That's a thrill."

and he wrote in Rolling Stone magazine in 2016:

"I’ve read (The Hair of Harold Roux) four or five times. It’s a couple of days in the life of this guy, Aaron Benham, who’s writing a book about a man who is writing a book. It’s this little house of mirrors. I love it because it tells the truth as I understand it about what it is to be a writer."

Professor Williams taught creative writing at the University of New Hampshire when I was an idealistic and romantic (the cynic in me also adds: naive and immature) undergraduate in the late 1970s. I majored in English, my focus being creative writing and British literature, while I cobbled together the necessary prerequisites of a pre-med student (i.e. my "back-up" career choice). My dream, however, was to be a writer of stories of wonder like those that had so enchanted me since a child.

However, writing genre fiction (as oft told by survivors of the times) and sharing it with my fellow English majors at our story workshops was akin to bringing pork to Passover seder. After nearly three years of patient disdain for my nascent tales of SFF, despite my focus on "character" and "theme," those two story qualities that my classmates and professors considered the quintessence of worthy literature, I finally crafted a tale that was overall well-received by my classmates, but their general consensus was that I was wasting whatever talent I possessed in writing SFF, and that I should focus on writing fiction that mattered (i.e. "literary").

After this class, Professor Williams asked to see me in his office. Expecting similar remonstration like those of disapproval I'd received from my prior writing professor John Yount (who I greatly admired and still earned an A- from, btw), I settled in the chair before Tom's desk while he thumbed through my semester's submissions. I must have looked pitiable, but he closed my student folder, sat back, and told me the following story. How much of it is true, I cannot say, or even if I recall it 100% correctly, but here it is. Professor Williams told me:

"A young man came to my door and asked if I would read his novel. The day was hot.

He was dressed in a torn t-shirt and jeans. Looking past him down my walkway,

I saw a idling black truck with too many miles on it, and the shadow of a woman inside

the cabin, her arm resting on the open passenger door window. I sighed and, feeling

sympathy for the young man, I agreed to read his manuscript. A week later, he returned, and I informed him that he had skill with writing, but the audience for such a work was very narrow. I handed him his manuscript and wished him well with it.

"Time passed, and when next this young man came to my door, he was wearing a tuxedo. He and his wife picked Elizabeth and me up in a limousine to join him for a celebratory evening. The young man was Stephen King, and the novel I read was 'Carrie.'"

This was the essence of Professor Williams: he was kind, inspirational, and supportive. Of all my writing professors, he alone ventured into the borderland between literary and fantasy fiction, touching upon it in his award-winning The Hair of Harold Roux and a spin-off from it entitled Tsuga's Children (1977) which he wrote for his own children. Of Tsuga's Children (and novels of its like), Mr. King wrote in Danse Macabre (p. 259):

"(It is) one of those books about childhood...that adults should take down once in a while not just to give to their own children, but in order to touch base again themselves with childhood's brighter perspectives."

While I soon turned away from writing to pursue a career in medicine (a Hobson's choice as sensibility insisted I select a profession with greater promise of putting food on my table and providing for a future family), I never forgot Tom or his story/parable that was both encouragement and humble acknowledgment of the fallacy of one's presumed certainty of anything in regard to what readers want. It is a lesson still relevant when considering the balance between writing what one loves and what editors/publishers/readers purportedly want. There are audiences for everyone.

Sixteen years later, on June 30, 1996, I met Mr. King at what I perceived as a paying it forward and paying back book signing that he provided, sadly in vain, to sustain Bookland, a struggling Maine bookstore chain that had strongly promoted and supported him as a young author. Reservations for the event were $50 and included pre-release copies of Stephen's The Regulators and Desperation in a combined package, a signed bookplate, and a numbered place in line (mine was #210 which was near the front).

The line coiled around the store. Ushers informed us that Mr. King would sign two books and that he would not have time for conversation. I would have preferred to have Mr. King sign my first edition The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger (1982, Donald M. Grant) which I had purchased at Bookland over a decade before, however, understandably, only books purchased in-store would be signed.

The line wound forward past displays of of Mr. King's works. I owned nearly all of them, mostly his novels. Thus, I picked up his short story collection Nightmares and Dreamscapes and felt a bittersweet hollowness in my chest when I read the dedication (above) to Professor Williams. Having been lost to the rigors of medical school and residency, I had not known that Professor Williams had passed away. It left me a bit shaken and strummed that easily reachable string of Jewish guilt--here for having lost touch with him and, also, of my choice not to further my own writing.

When I reached Mr. King, he greeted me with a generic smile and reached for the book. Upon seeing its title, his expression turned quizzical. Among the plethora of Carrie-s, The Stand-s, The Shining-s, and Salem's Lot-s that he'd autographed, I suspect this particular book had not yet been passed to him for signature. In answer, I said only that Thomas Williams had once been my writing professor and how much I cherished his memory. To the surprise (and annoyance) of the ushers and the waiting King fans behind me, the line stopped. Mr. King and I shared a conversation about Tom, paying off our respective if different debts to this good man.

In the best written works, time stops a moment when something genuine is shared. Quickly, however, the hubbub of the crowd rushed back upon us. Time with its duties and obligations resumed, and I moved on.

As with great works, so with the great people who made impressions intaglio upon our lives. Here is made evident the truth in the traditional saying among Jews which

we say for the departed:

"May his name be as a blessing."

Comments